This week’s toy: a CT scan of Lego Minifigs. It turns out there was some pretty good engineering inside those small plastic things that prevents them from being crushed when you accidentally step on them and think they’re made of steel. Edition No. 69 of this newsletter is here - it’s November 22nd, 2021.

The Big Idea

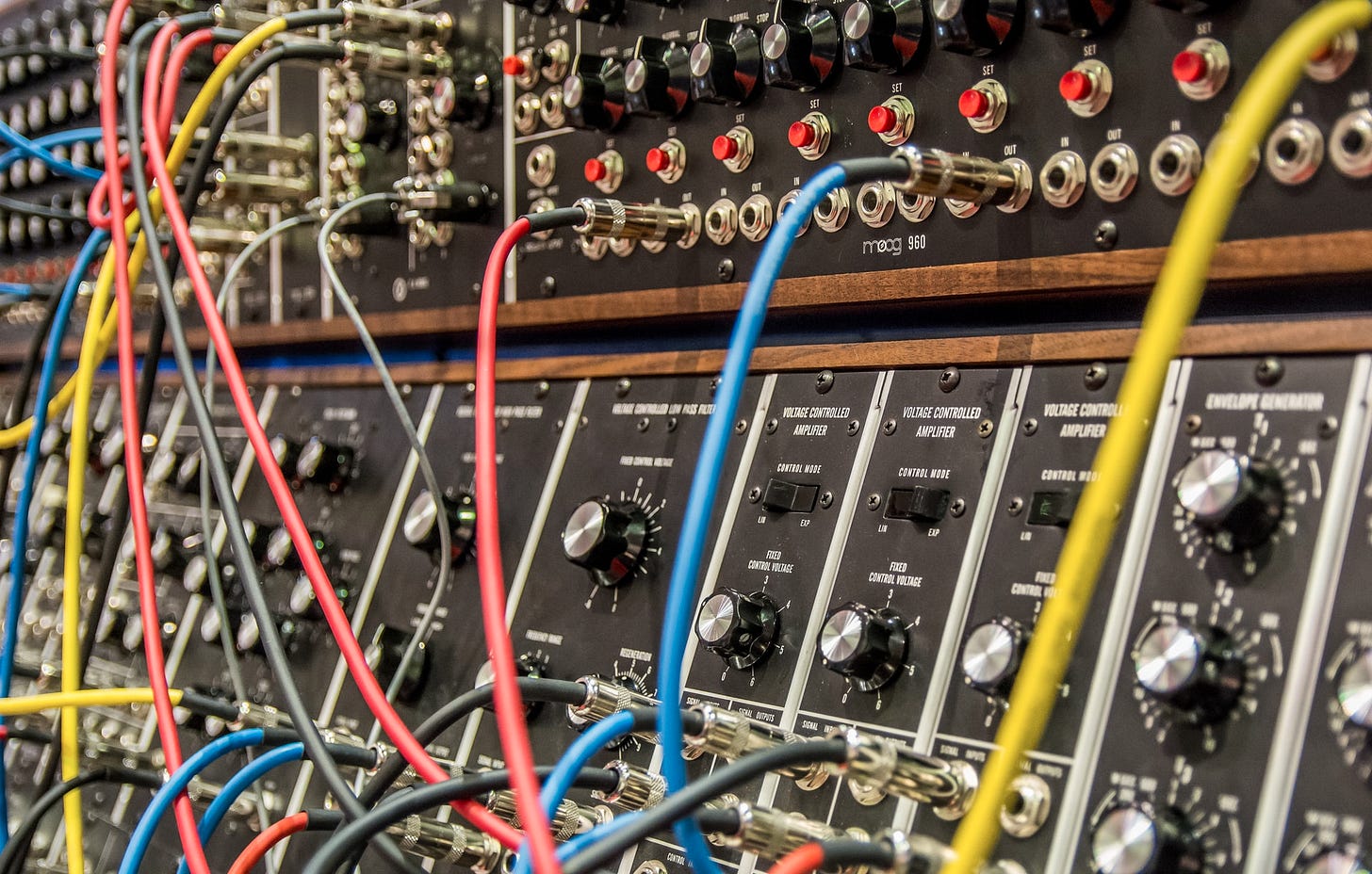

It’s easy to look at the data and decisions in your organization as a bunch of spaghetti code. Who knows if pulling out the blue plug and moving it two sockets over will produce a desired result, or a missing signal at an important point in your business?

Connectivity ≠ Alignment

I believe the fundamental disconnect here is the lack of alignment between metrics (the data we are watching based on activity in systems) and visualization (the way we show those metrics and discuss them). If we show information without context, we get weird results.

Pretty visualizations without a connection to underlying data may be accurate, but lack context.

Take this lovely example (seems topical, as Thanksgiving is approaching) of a Pie Chart about Pie.

In the satirical example above, the pie chart renders how much pie has been consumed. But what does it mean? There is no time series of the pie. We’re not sure of the impact of consuming pie in the visualization.

Putting this pie in the context of Thanksgiving dinner might provide additional ideas, even as a joke:

What % of calories consumed at a holiday meal are dessert?

What kind of pie is the favored choice of households by region, year over year?

What are the input costs of the pie?

How would the consumption change if the cost of lemons, sugar, and eggs accelerated at different rates?

How do the diners feel after they eat pie, and do the rest of their activities improve after Thanksgiving or do they struggle to recover from their turkey-induced overindulgence?

The bigger point here is that the chart above is a point in time (after you’ve consumed too much pie). It misses the story managers need to run their business.

Metrics need to be atomic

The key thing you need to know about your metrics is their definition. For the entire duration that you are tracking a thing, you need to know “how did we do that.” And that metric shouldn’t change. When you change a metric, you are changing assumptions, inputs, computation, and outputs. That basically means you are creating a new thing.

Does this mean you should never compare the vNext version of “Annualized MRR” with the vPrevious version of MRR of “Annualized MRR”? Nope.

You need to make it very clear to someone:

What were the inputs to the metric?

How did you calculate it? Is it a summation or aggregation? Does it depend upon one system or multiple systems?

What systems or fields does the metric depend upon, and what is the expected data type and validation for those fields?

What are some lower bounds or outliers that would cause you to question this metric?

What are some upper bounds or outliers that would cause you to question this metric?

When was the last time this changed, and who owns it?

If there is a time series of this metric, what is the lowest common denominator where you would trust original information (for example, if you collect data weekly, beware of a representation of this metric that promises “daily data” without calling it out as an approximation or sub sampling)

Adding this metadata to a metric, along with a description of where the metric fits in a time series, makes your metric atomic. With one unit and one measurement of data, a reader is able to make a true inference about the underlying data and have some context about who owns it, where it came from, when it was collected, and how it *could* affect other data.

Visualization changes depending upon expectation

Many people refer to dashboards and metrics as an expression of form.

“Show me the week over week series of opportunity data”

“How many leads did we get this month?”

“Is our funnel conversion working?”

These are the kind of questions you might get when talking to revenue or marketing operations leaders within your company. What you don’t always get is questions about the validity or correctness of that data, until there is a “What-if” scenario posed to the group.

“What if we added a few more account executives selling at the same rate?”

“Is it possible to find a source of web traffic that converts better”

“Why is our funnel conversion working, or where is it not working?”

Now that you changed the expectation from tell me what happened to explain why something happen, and model the sensitivity of the inputs and outputs for explaining it might change, you moved from a simple line graph into multivariate analysis.

A better dashboard or report would give you the ability to ask your data questions like this, and provide guardrails for the questions you asked. It would be able to tell you the meaning and composition of a metric. It would tell you the last time an important event happened in your company that might have influenced an input in the very dashboard you’re viewing. And it could help you align your “what-if” questions with different outcomes from the past, near-present, and future.

What’s the takeaway? Making your metrics stand on their own and provide a narrative gives you the freedom to build a narrative story from your visualizations. With a clear-eyed view of data and how it depends on different systems in your company, you’ll have a better chance at communicating how (and why) things change.

A Thread from This Week

Twitter is an amazing source of long-form writing, and it’s easy to miss the threads people are talking about.

This week’s thread: a manifesto on improving our supply chain infrastructure.

Links for Reading and Sharing

These are links that caught my eye.

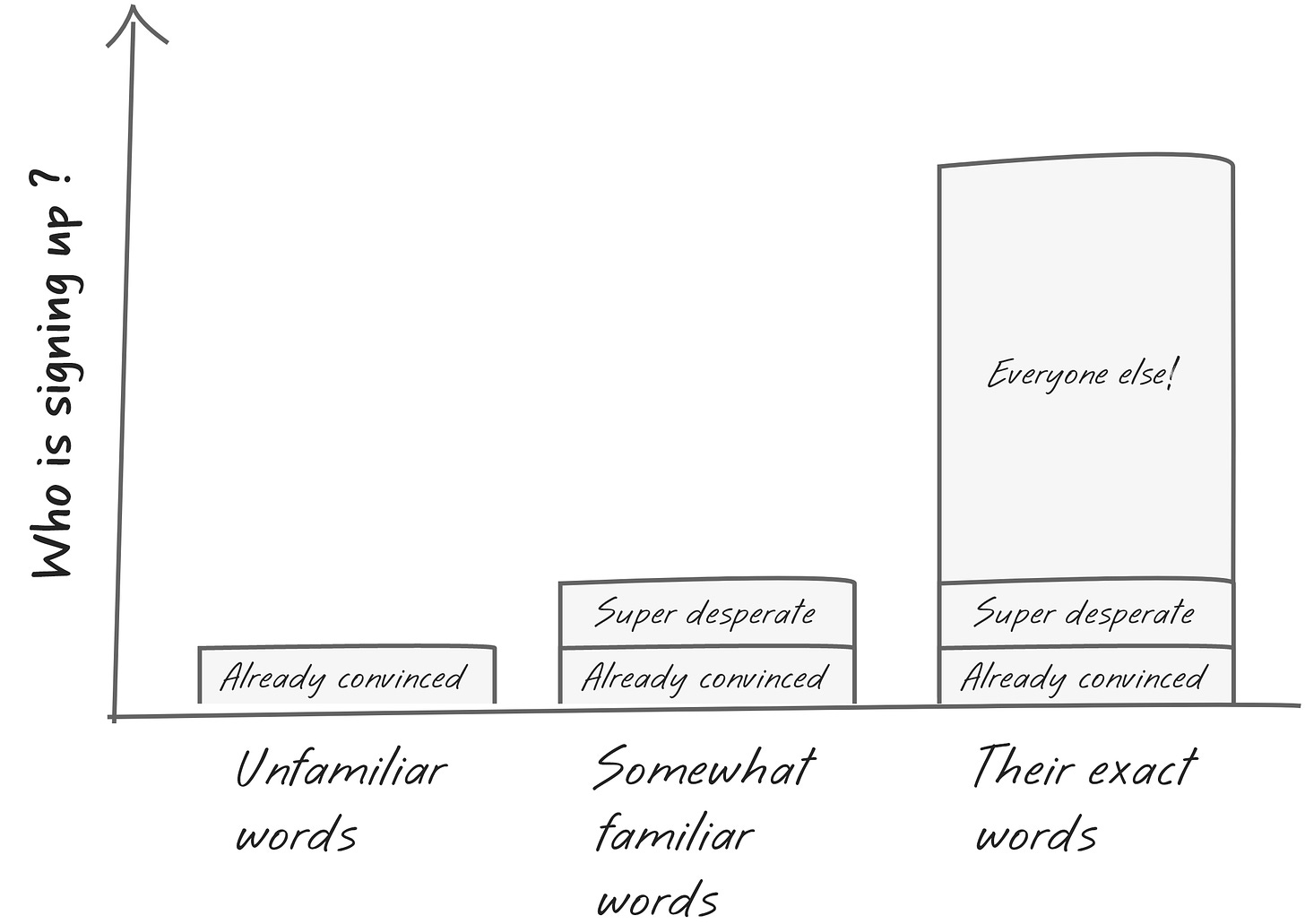

1/ Watch your words - It turns out that language is one of the most important ways to improve the success of your startup. When someone arrives at your website and does not understand what you do, they leave. This is akin to the “coffee shop line balk” response when people see a wait time that is longer than they expect. Don’t be that coffee shop.

Make it easy for prospects to understand what you do. Using the words of your prospects is a superpower.

2/ Save while spending? - There’s a new way some governments are encouraging people to save for retirement: think of it as tipping themselves while they spend other money. This method of saving while spending is a behavioral hack to get people to think well of their future selves at a time when they are already choosing to save money. A corollary here is to allow vendors (and governments) to add money to this future benefit (cheaper in today’s money than in the future) and you have an interesting market signal.

3/ Why is Real Estate so expensive? - Of course, it’s location, location, and location that govern the desirability of most real estate out there in the market. When you look at a neighborhood, you are assessing the house to evaluate, the nearby houses, and whether a group of houses seems like a viable community. Why not increase the number of viable communities, asks Daniel Herriges? The data suggests it’s easier to create more desirable places to live than to expand the existing ones.

On the Reading/Watching List

Reading: Status as a service. This 2019 article is more relevant than ever in a world where you need to assess whether someone really knows how to do what they say they can do and you’ve never met them before. Traditional models of credentialling don’t work. New models like crypto are … well … dependent upon whether you believe in crypto. There needs to be an intermediate step between “you say you can do anything” and “this NFT proves you can do anything.”

Watching: Tick, tock … BOOM on Netflix. I didn’t know much about Jonathan Larson and thoroughly enjoyed this biopic from Lin-Manuel Miranda. Who knew Andrew Garfield could sing?

What to do next

Hit reply if you’ve got links to share, data stories, or want to say hello.

I’m grateful you read this far. Thank you. If you found this useful, consider sharing with a friend.

Want more essays? Read on Data Operations or other writings at gregmeyer.com.

The next big thing always starts out being dismissed as a “toy.” - Chris Dixon