We need a better way to select software

The B2B software selection process doesn't help you to figure out which job you need done. How could it be better? Read "Everything Starts Out Looking Like a Toy" #149

Hi, I’m Greg 👋! I write weekly product essays, including system “handshakes”, the expectations for workflow, and the jobs to be done for data. What is Data Operations? is a post that grew into Data & Ops, a team to help you with product, data, and operations.

This week’s toy: an analog computer with physical switches and dials. What better way to learn how logic gates work than to snap a switch from here to there? It’s also an interesting modality for future computer safety, where non-motorized switches might provide a kind of fail-safe against unwanted computer activity. Edition 149 of this newsletter is here - it’s June 12, 2023.

Brought to you by Pocus, a Revenue Data Platform built for go-to-market teams to analyze, visualize, and action data about their prospects and customers without needing engineers. Pocus helps companies like Miro, Webflow, Loom, and Superhuman save 10+ hours/week digging through data to surface millions in new revenue opportunities.

If you're reading and haven't subscribed (yet), give it a try! And if you have any comments or are interested in sponsoring, hit reply.

The Big Idea

A short long-form essay about data things

⚙️ We need a better way to select software

Imagine that you are starting a B2B SaaS company and you are thinking about setting up your software stack to get going.

Certain items are non-negotiable, as you have prior experience with a tool and might be an expert, or it’s just so obvious that you should pick software X over software Y.

Except when it isn’t as obvious.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of vectors to consider in that decision:

Cost - how much will this software cost on a monthly or annual basis

Complexity - is this a simple or complicated problem to model and solve, and does it require external resources beyond the implementing team

Integration - does the solution require integration (bespoke or otherwise) with existing tools, and does the data model of those tools support that integration in the intended function

Jobs to be done - what task or series of tasks are we asking the solution to solve and what value do we expect to be delivered from that process

Ease of use - what will it feel like to use this software on a regular or one-time basis

Current knowledge - does the team know how to use this software or is it a brand-new experience for them

There’s a lot to think about when you need to find a solution to solve a problem, so what’s a business user to do when finding prospective software?

Search, then ask a friend

I did an informal LinkedIn poll (don’t worry, I’m not trying to be scientific, but looking for directional information) where I asked readers to pick how they would research this question.

The answers fall into a pretty common pattern. Search, talk to a friend, and identify customers of that software are the most frequent answers in a limited set of poll options.

Great plan! It’s not so easy to implement in practice, which is one reason firms hire teams to help them solve this tool selection and implementation process.

Answering the question of the “right tool to pick” depends on a match of your needs to the output of what job the product does, how the product does this job, and perhaps even why it does it that way.

This is a framework shared by Kit Ulrich, who gives an example to describe Amazon and its JTBD delivery to B2C customers.

Are you a consumer looking for a book? Nope, but the basic principle is the same:

You need software to solve a problem for you. That problem is likely something pretty specific, like “track sales made by your company” or “calculate the commission to send to salespeople” or “send a message using the internet to another software system with information from this software system”

You have a specific way or ways this product needs to behave. It might be as mundane as “can access it on a mobile device” or as complicated as “wait for another system to tell you to proceed, and then run a series of custom code elements.”

The specifics of how the product needs to accomplish this are usually important. Based on the “how” that this product behaves, it may cause downstream effects that govern how your other software stack will work.

So why is it that when you ask skilled integrators about their clients in the software selection process, one of the common threads that show up is that “business users don’t know the questions to ask?”

The current process is too random

Searching Google doesn’t mean “searching with the demonstrated ability to find the right answers to inform other questions.”

Talking to a friend doesn’t mean that friend has any clue how to solve that problem.

And customers who use that software have gotten there by a variety of pathways.

Some of these “choose your own adventure” pathways turn out great. Others, not so much.

There isn’t a standard way to know if a software package is right for you, and competitors are likely to look quite similar when you compare each one of them on basic capabilities. (There’s a silver lining here, which is probably that you have the chance for many software selection processes of ending up with an ok solution even if you’re not sure what you’re doing.)

You might also be setting up a situation where later an implementer is going to need to take a heroic effort because the initial selection process was incomplete.

How could this be better?

Search better than “find a G2 grid and get a demo”

Your project is unique, but the capabilities required to solve that project are not.

As a business user, you’re doing the best you can with the knowledge that you have about that problem space. If you have experience in the space because you build the implementation at your last company, you have an unfair advantage over people who’ve never used it before, but you still need to size and build for your current situation.

The information to answer that question is distributed and not readily available when you use a typical search process.

Business users and operators are aggregating information from many places, including these and others:

Social Review sites (G2, Capterra)

Search Engines (Google, Bing)

Friends (some who know what they’re talking about, and some that don’t)

Industry experts in expert communities (WizOps, RevGenius, and other Slack and Discord groups)

Customer feedback (ranging from happy referenceable customers to disgruntled back-channel conversations)

There’s a lot of seemingly unrelated information that needs to have more of a standard schema to compare the Job to be Done, the Software you’re considering, and the suitability to solve that problem given your environment.

Using one of these methods to research gives you a decent solution. I think we can do better.

Dear LLM, please make me a solution

It would be great if ChatGPT or another bot could solve this problem. The answers you’ll get today are pretty formulaic and don’t give you the kind of depth you would expect from a robust exploration of this issue.

A perfect solution for this software selection process might look like this:

A structured interview process that helps you refine the reason you are trying to evaluate or buy software into a Jobs to be Done statement making it easier to line up potential solutions into an equivalent comparison

A written process to cross-check your output to make sure that you haven’t missed critical items in your discovery, and an ability to collaborate with the rest of your project team to validate the problem statement

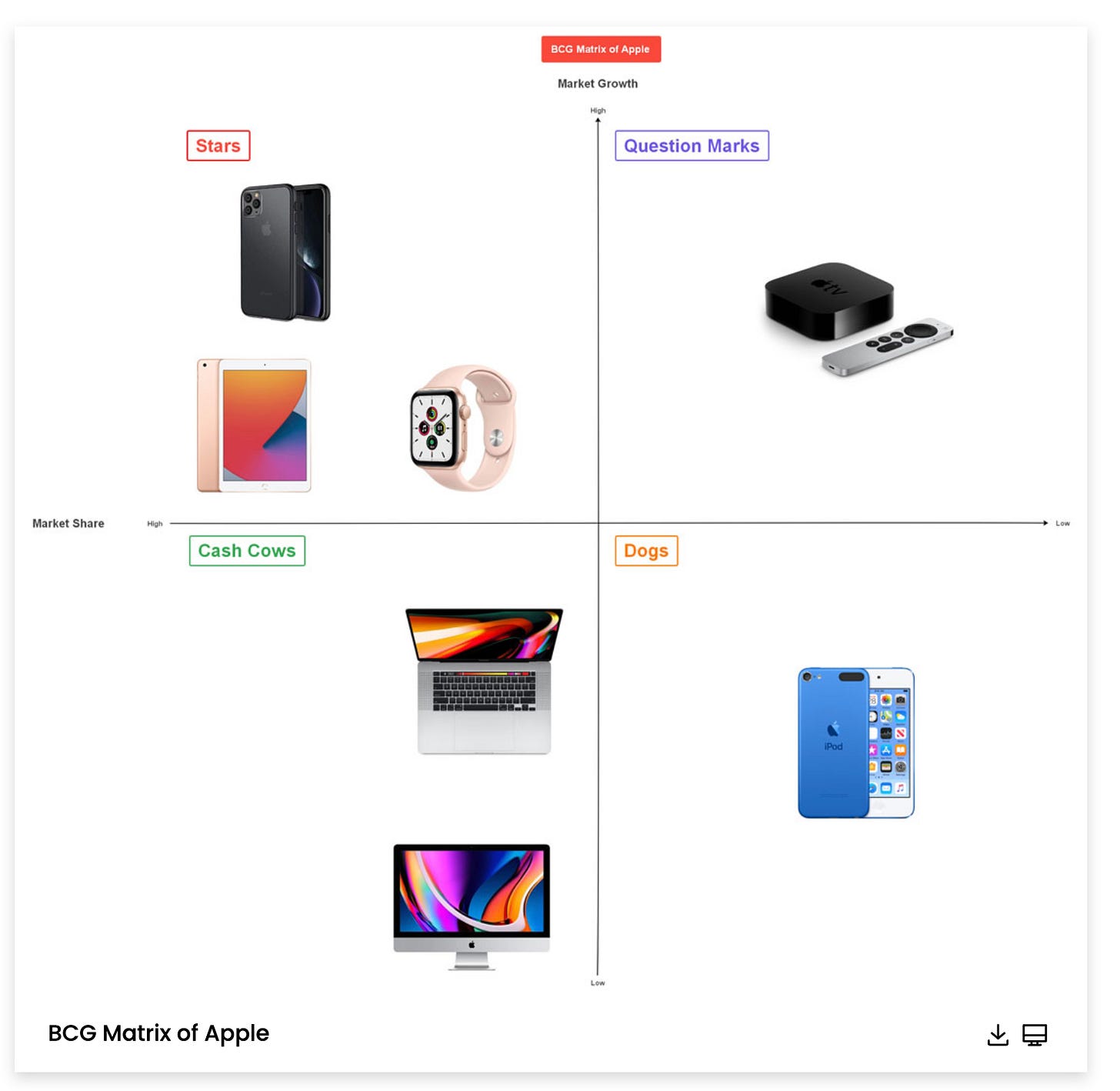

The visual output of a 2x2 matrix with considered vendors graphed by the relative strength of that company along the axis you mentioned. You could use products, logos, or capabilities to map the axis you are trying to display

Here’s a sample of this form of comparison showing Apple products.

For a particular job to be done (perhaps in this example, identifying the most profitable product lines by growth and market share at a consumer products company), there are products and services that meet that criteria.

What’s the output of your software selection process?

The combination of a visual output containing logos and product names and a more quantitative, score-based output will help sell your idea internally and to negotiate with software vendors.

It will also keep you grounded to remember the reasons you originally went to the market to find a solution.

What I’d expect to see:

A table with a summary of information needed to understand the Job to Be Done and how we are evaluating potential solutions, including time, capability, cost, and expected complexity

A project brief detailing the summary, steps, and timeline to achieve this goal

And perhaps … a list of people who could solve this problem for you based on peer-reviewed results.

Imagine that you could take a grid like the one below at G2 with 800+ software vendors for CRM and filter it for your specific needs, not just by Company Size or Standalone/All in One filters.

That would be pretty cool 😎.

We’re basically talking about a structured process for identifying a need, sourcing vendors, and evaluating a solution to the software selection.

It’s what we expect from management consultants, but why can’t we do it better ourselves?

What’s the takeaway? The information to run a better software selection process that’s customized for our particular Job to be Done is out there in the market, but not yet easy to search, collate, and analyze. There’s a big market opportunity to make this better, along with the potential to teach business users “how to fish” when scoping, procuring, and selecting software to meet their needs.

Links for Reading and Sharing

These are links that caught my 👀

1/ Define ICP, then refine it - “Determine which customer segments are successful with the product and then figure out how to optimize the go-to-market strategy to acquire these segments profitably.” -Mark Roberge’s advice on how to improve your funnel focuses on what to do once you have had initial success in winning deals.

It turns out that some deals are better than others, and understanding the ones that are the most profitable (and finding more of those) is one of the most high-value exercises we can do.

2/ The promise of wireless energy - The way Ali Hajimiri explains it, we have waves all around us. We perceive some of them as light, some as sound, and some as energy. Since other forms of communication have moved from wired to wireless, why not other forms of waves? Hajimiri’s research shows that coordinated waves of wireless energy can be created without physical switching, simply by changing the timing of the energy pulse.

Yup, it’s mind-blowing if it works and already seems to be in the works to commercialize. In small installations, this could enable you to direct power from a single place to multiple areas of your home. At a large scale, this could be a potential source of energy from space (sounds a bit too easy to weaponize, so this will need to be safeguarded).

3/ United States of 🍩 - If you are a donut connoisseur, you might have a favorite place to find your snack food. In certain places in the United States, that definitely means Dunkin Donuts (in Massachusetts, you’ll likely hear Dunkin locations used as waypoints for directions). But in other parts of the country, the market is a bit more fragmented. The Washington Post has a helpful guide for you!

What to do next

Hit reply if you’ve got links to share, data stories, or want to say hello.

Want to book a discovery call to talk about how we can work together?

The next big thing always starts out being dismissed as a “toy.” - Chris Dixon